30 Artists, 30 years – Dr Nassar Mansour

BF: The Foundation was delighted to invite you to teach classes on Islamic Calligraphy at The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in 2016 as well deliver a talk on the subject as part of the Open Programme at Asia House. In addition, we supported a solo exhibition of your work in Dubai in 2017. The Foundation is a big fan of your work, in fact, you are still a Master teacher for Alka Bagri to this day. Why do you think it’s important to continue teaching Islamic calligraphy today and what do you personally get from it? You’ve mentioned that most of your students come from the world of Islam. Why do you think the art of Arabic calligraphy has mostly stayed within those from an Islamic background?

NM: The art of Arabic/Islamic calligraphy in the broadest sense is an art that is associated with the Divine Word of God, Islamic Culture and Civilization, used to copy the Holy Quran and used also to decorate architectural facades and surfaces of a wide range of objects and materials. Art of calligraphy reached its zenith through copying the Quran and teaching and practice until it became the first art of Islam.

This art, which is based on Arabic letter forms, has attracted many non-Muslims, whether Arabs or non-Arabs. In addition to talking or writing about it with love and admiration and passion, there are also many people who are deeply keen in acquiring calligraphy artworks, whether old or contemporary, and love to see the beauty of their meaning, their letter-forms and their good composition.

I remember that when the trustees of the British Museum decided to honor the former Museum director Dr. Neil MacGregor, he asked for an Arabic calligraphy artwork in a specific text from the Holy Qur’an and asked this text to be written by me. It was a great privilege for me! I did the work and it was an unprecedented piece with a composition that reflects the concept of the text.

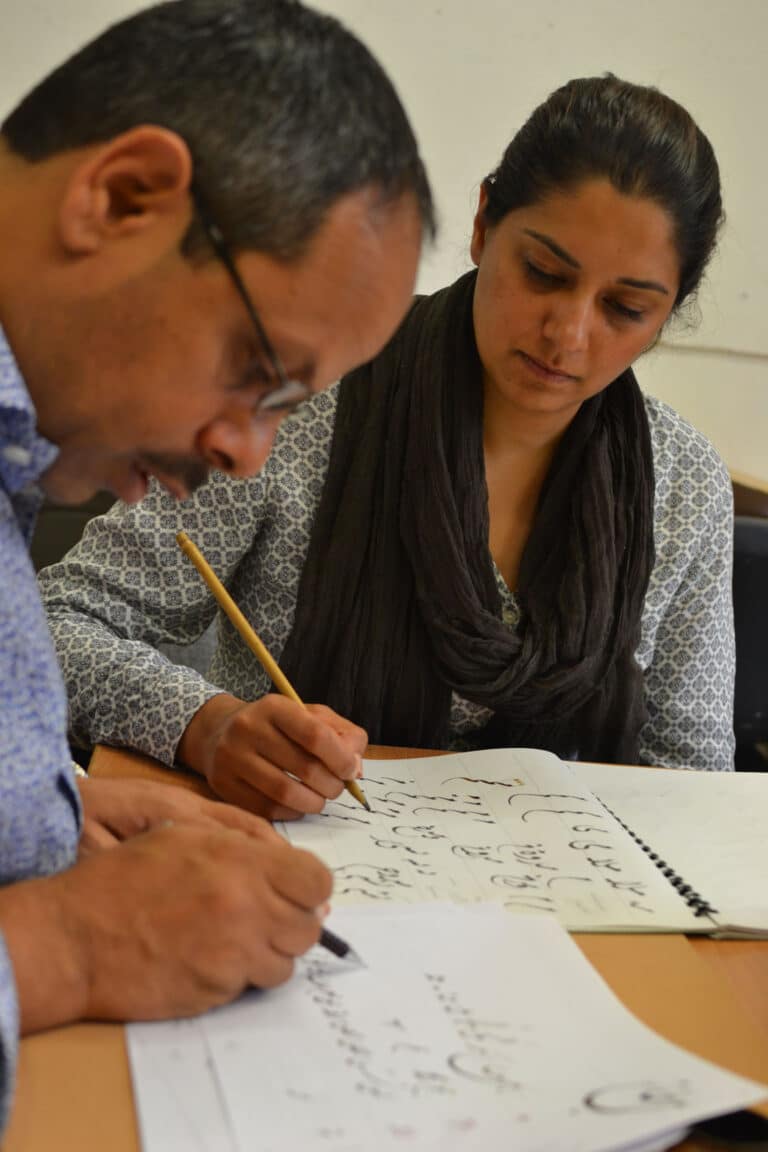

The love of non-Muslims for Arabic Calligraphy has even exceeded that. Many are attracted to the beauty of calligraphy and it’s letter forms to the point that they started practicing the art without even a basic knowledge of Arabic language. I know many non-Muslims who came to my calligraphy courses at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts here in London.

One of the examples worth mentioning that I know through my courses is the case of Mrs. Bagri, who is non-Muslim and of Indian origin, but she loved the art of Arabic calligraphy and began learning it in 2015. To this day, she continues to practice with love, passion and patience and now she is practicing to achieve the traditional Ijaza – an authoritative calligraphy diploma given by a master – in the art. Soon she would be the first non-Muslim woman, to my knowledge, in the world to obtain this diploma in the art of Islamic Calligraphy. This confirms that Islamic Calligraphy is a universal art, and not confined to Arab or Muslims.

BF: Your work on the word Kun (‘Be’ in English) managed to bridge two quite distinct fields – traditional Arabic calligraphy and contemporary art. At the Foundation we try and encourage such cross over disciplines and geographies. Is your current work pursuing this in any way?

NM: The artist should be up-to-date, making sure that he refers to the right traditions of any art. It is not enough to know the traditional rules and basic style of calligraphy, but we must move this art forward to other levels, of course, with maintaining the true essence and spirit of the art! There are many of my artworks that are presented in a contemporary appearance, but at the same time, still has the spirit of the tradition, just adding another dimension to the work by reflecting the meaning of the text through the composition. I could mention, for example, the 99 Names of Allah and Huwa, which was also done in bronze.

BF: As a leading thinker of Islamic Arts and an award-winning academic and artist, what elements of this field of study do you think remain most relevant to those researching and practicing during this difficult global crisis and to the future ahead?

NM:. The art of calligraphy remains a wide field for researchers, whether Arabs or non-Arabs. There are many studies and research works presented by academics and researchers from different backgrounds and in many languages. But there is an important point that must be mentioned, that the field of research must be based on the art practice, because many studies, research and articles come out shallow with no depth, and sometimes with mistakes. The reason behind that lies in the lack of real knowledge and experience in calligraphy that comes through practice. For example, the researcher cannot talk about the calligraphy pen, which is the primary tool for calligraphy, unless he has tried preparing it, knows its qualities and how to hold it correctly for writing and experience the writing. This also applies to calligraphy paper, ink and so on … These fundamental details give the researcher a broad and deep understanding when he talks about the pen or anything related to the art of calligraphy. To cross towards a new dimension of calligraphy, practitioners should understand the art deeply, practice it with love and knowledge.

Biography

Dr Nassar Mansour was born in Amman, Jordan 1967. He obtained a BA in jurisprudence and legislation (Islamic studies), economics and statistics from the University of Jordan, 1988 and graduated with an MA in Islamic arts, specializing in Arabic calligraphy, from the Al al-Bait University, Jordan, 1997. He was a lecturer in the art of Arabic calligraphy at the University of Jordan from 1991-5, and later at the Faculty of Traditional Islamic Arts, al-Balqa’ Applied University, Jordan, 1998-9. From 1997 – 1999, Mansour was in charge of calligraphy and ornamentation on the project of rebuilding the twelfth-century Saladin’s pulpit (minbar), which was destroyed in 1969, at the al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem. In 2003, he received a calligraphy diploma (ijaza) from renowned Turkish master calligrapher Hasan Celebi (b. 1937). He has participated in and delivered numerous calligraphy workshops and exhibitions in the Middle East, Europe, India, Malaysia and Japan. Mansour’s work includes publications on calligraphy and the ijaza and he has organised an exhibition on the ijaza, ‘The Making of the Master’, with Venetia Porter at the British Museum, in 2005. He earned his PhD at the Visual Islamic and Traditional Arts Institute (VITA), London.