30 Artists, 30 years – Farhad Ahrarnia

Interviewed by Isabelle Caussé, art curator, Bagri family collection – April 2020.

IC: The Bagri family collection holds a few of your works from two different series each showing an interest in craft. Is this an important aspect of your work?

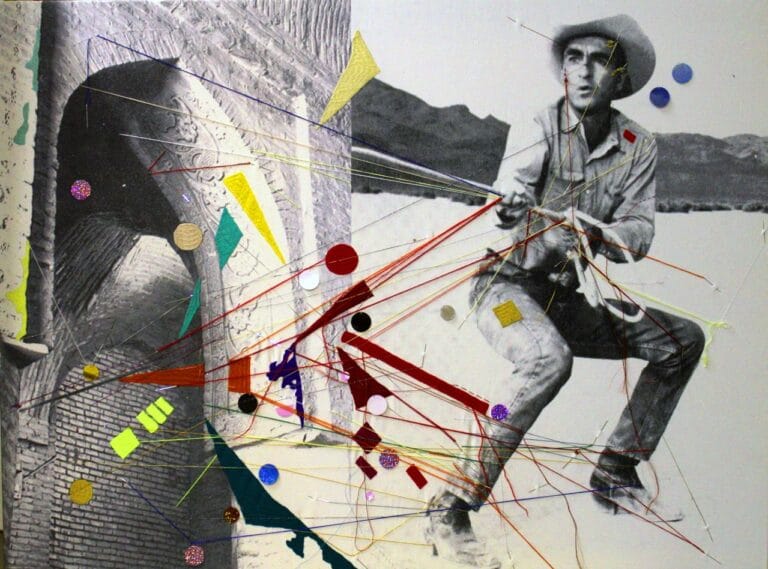

FA: I come from a very hands-on approach to film-making, pre-digital, when we were only using 16mm and 8mm films. Rolls of film were mechanically shot and chemically developed, and for the purpose of editing strips of film would be cut, spliced and re-assembled. This process felt very sculptural and tactile, physically demanding yet rewarding. The hands were very involved in this process and one could sense the physicality of making a film. In many ways creating a cinematic work was a major craft, and it still remains as such to a great extent. So, cinema played a great deal in my training and understanding of creating illusions and sensations which were mainly visual and sound based. When I gradually moved from making films to exploring photography as a medium, I became interested in the physicality and tactile qualities of photographs as objects. The application of embroidery onto the photographic is my way of enhancing and complicating the sense of ‘sight’ with that of ‘touch’. As Carl Jung famously said:

‘Often the hands will solve a mystery that the intellect has struggled with in vain’.

So, for me, there is plenty of refined knowledge embedded and transferred through the hand-made and craft-making practices.

IC: You live between Shiraz and Sheffield. Is your daily work guided by where you are?

FA: For me these two sets of geographies are now fully melded into one, conceptually at least. I have learnt a lot from the many layers of history of ideas and transformations which these cities/localities have gone through. Particularly the destruction of Sheffield during the Second World War, its manufacturing legacy, and its ongoing social struggles. In many ways my works are a set of very direct and raw responses to specific qualities which these places possess, and what I learn and draw from them on a day to day basis.

My response to contemporaneity of Shiraz is much more immediate and urgent whereas the connection to Sheffield feels more and more romantic and subliminal, and I am very interested in understanding that within myself. I find Shiraz very dynamic and optimistic. The city functions like a sponge, continuously absorbing ideas, technology and new inhabitants with high aspirations. There is a complex bazaar and a network of commercial distribution centres, with hundreds upon hundreds of small businesses and workshops spread across the city. It is very viable to set up a workshop and make useful and beautiful objects. It is much easier to survive as a small business, and particularly when it comes to craft-making practices, the local government has a large budget for supporting and subsidising the activity of artisans with high quality, such as access to rent-free workshops and fairs. On another hand, Sheffield is still dealing with the long-term neglect and that bitter and very rigid dichotomy of the North and South divide, which still very much exists in England, unfortunately, this is very palpable when you spend time in that city. Craft making practices are treated as a luxury in Sheffield but more of a necessity in Shiraz, maybe because many people’s incomes depend on it and the practice is widespread.

As makers of art objects, one is always dealing with the surrounding possibilities and the limitations, if anything it is those very obstacles, which offer the greater challenges, both formal and philosophical, that lead to the creation of more considerate works, which are ultimately very personal. For example, the making of the Dustpan series directly comes from my mother’s interest in silver works made specifically in Shiraz, and my memory of growing up with these objects. I guess one develops an understanding of the complexity of these objects and starts to think of the potential to push the possibilities. How to utilise the expertise and the logic invested in these local techniques, and the qualities which have been passed down from generation upon generation. These types of knowledge and expertise cannot be learnt from books but only through the tradition of apprenticeship. Therefore, making of the dustpans was very much dependant on being in Shiraz and working with a master engraver/silversmith. It is the same for my embroideries and other woven, carved or constructed objects, they all depend on specific local knowledge and the expertise of those who have mastered their art.

IC: Can you say a bit about contemporary creativity in these two cities and perhaps any wishes for a project to bring them together?

FA: Both cities have an extended art, film, theatre and literature scene that manifest in various pockets. There are long standing artists living and practicing in these localities, some with international reputations others carrying on indifferent to fame or recognition. What is important to recognise is the ongoing formation of knowledge and the long-term legacy of these cities. Sheffield being at the heart of Industrialisation and the creation of massive amounts of wealth, artisanal expertise, knowledge-making, and political consciousness and resistance. Shiraz for an untiring spirit of renewal, transformation, and adaptability to the spirit of times whilst maintaining her classical values and traditional traits and profundities which have been passed down and heavily guarded through centuries of renewal and rebirth.

I do feel extremely privileged to have access to the craft-making expertise that exists in these localities and will continue to learn and explore the possibilities. I intend to explore the making of ceramics and learn from traditions of treating iron and carving onto precious stones, practices that are still very vibrant in Shiraz. If anything, however, there is more urgency for me to learn from craft making practices in the North of England, such as working with silversmiths in Sheffield or stonemasons across Yorkshire, which are diminishing due to lack of patronage and funding. Indeed, I would like to be able to transfer some of these skills to Shiraz or at least collaborate and learn from them directly.

Biography

Farhad Ahrarnia is an Iranian-British artist, based in Shiraz and Sheffield. He adopts and draws knowledge from an extensive variety of craft making techniques relevant to his localities. Through a rigorous methodology of referring to art historical references, particularly those of Sagha-Khaneh, Russian Constructivism and Surrealism, he continues to dissect and re-articulate the spirit and experience of modernity and modernism in contexts other than exclusively Western. Thus complicating and interrupting the established art historical categories, narratives and dichotomies. His art works are kept in numerous private collections internationally and are part of the public collections of the Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford, the British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Los Angeles county museum [LACMA] and the Museum of Western Australia.